I didn’t. So Marlie Tilker, chair of the Dunvegan Museum’s Glengarry Honey Fair committee kindly dropped one off a few weeks ago. It turns out that bee houses(also called bee hotels or bug hotels) are not intended for honeybees. They are designed to attract native, ‘solitary bee’ species such as mason bees, leafcutter bees and miner bees. Unlike honeybees, these solitary cousins don’t live communally in colonies. According to an article on Almanac.com, the native bees are very docile and “up to three times more effective as pollinators.” While your bee hotel won’t produce any honey, your super-pollinating guests will contribute to healthier flowerbeds and higher yields from your vegetable garden.

For an idea of what one of these ‘hotels’ looks like, imagine an open wooden box that’s about 15 cm deep, with a simple roof with a 5-8 cm overhang to shed rain. As their name implies, solitary bees like to set up their nests in single holes. So, to accommodate them, the box is filled with nesting materials like cardboard tubes, short lengths of bamboo and scraps of wood, offering holes that range between 4–10 mm in size. For an idea of what the front of a bee hotel looks like, open up a box of drinking straws (paper, of course) and look down at the round ends. To prevent birds from snacking on the nesting holes, fashion a cover from wire hardware cloth fitted loosely in front of the bee house. Don’t put the wire mesh tight against the nesting holes; the bees need a little space to landing and take off. If you’d like to delve deeper, YouTube is awash with how-to videos on building your own bee hotel.

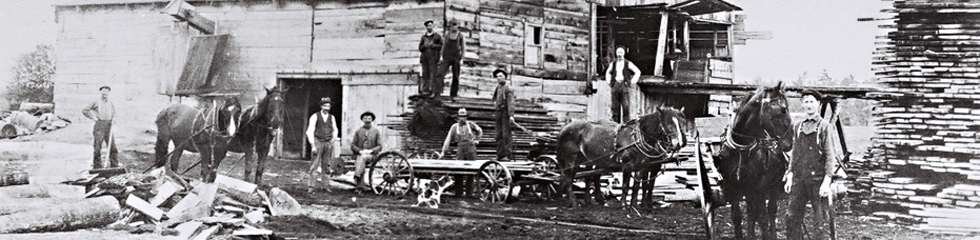

Or you can wait until the first annual Glengarry Honey Fair hits town on Saturday, August 13th. In addition to workshops on ‘beetel’ construction, the day will be devoted to the importance of bees, and honey, from pioneer time until today. For more information, visit the museum’s website: GlengarryPioneerMuseum.ca

Johnny C. & Old Dick

Reader Ken McEwen gets his Glengarry News via Canada Post, so his comments on my columns are usually one week out of sync. Nevertheless, his input is always appreciated. Following my piece a few weeks ago on Johnny Carpenter, Dunvegan’s beekeeper, Ken emailed to say that his most vivid memory of Johnny is of him sitting around Nelson Montgomery’s auto repair shop and filling station back in the 1940s. Nelson’s garage was attached to the back of the old brick hotel on the southwest corner of the crossroads and Ken says the two outdoorsmen would swap tall tales about their fox hunting prowess. As Ken pointed out, these were the days when fur coats were in fashion, and a fox skin was worth $15 to $20. “Doesn’t sound like much today, but it was big money then,” Ken remarked. And he’s right. The Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator estimates this would be $285 to $375 in today’s dollars. Ken also remembers that Johnny’s house north of the Dunvegan schoolhouse didn’t have electricity. That is until one Sunday (no doubt after church) when, in a random act of kindness, a hunting chum from Maxville with electrical knowledge turned up at Johnny’s front door with a group of helpers and wired it for free.

As for other beekeepers in the area — at least on the 7th or 8th concessions — Ken knows of only one: Richard Rolland. Known locally as “Old Dick”, he lived on the 8th, at the end of a very long lane. “I recall going there with my Dad for honey,” Ken wrote in his email message. “Dick didn’t have an extractor, he

just cut the comb out the racks, and flopped it into a large pot we brought.

My mother cut the comb into plate-sized pieces to serve. Was ideal, you

had a good feed of honey to accompany your toast for breakfast, and a chew

of bee’s wax to boot.”

The Dunvegan whistle

From time to time, I toss questions to Ken about life in these parts, back in the day. For example, while walking the dog one day last week, I agonized once again over how many Manitoba maples we had allowed to take root on our property. This led to my wondering if this invasive, weed-like species had also been around when Ken was a young boy. The answer is yes; there were some growing on the farms in his neighbourhood.

“A rather useless tree, it had no similarity to any type of maple,” Ken told me. “Only thing about it was it put up shoots from around its trunk, right about this time of year, when the sap is rising in the real maples.” It was because of this property that the Manitoba maple became part of a springtime ritual he and his childhood chums completed year after year: whistle making. Ken’s older brother taught him how to cut off a shoot from a Manitoba maple about the size and length of one’s finger. He would then notch the stick with a penknife, and then use the knife to make a cut through the bark that went all around the stick. Using the handle of the knife, he would gently pound the bark to loosen it. The next step was to give the bark a sharp twist and then slide it off. A few more swipes of the knife would flatten the area in front of the notch. And then all that was left was to slide the bark back in place. “And presto,” Ken related, “You had a whistle. The tone dictated by the size of the shoot. Big shoot, lower tone. Small shoot, a more shrill tone. Sounds sort of primitive, but it was a springtime ritual… one that is no doubt long forgotten.”

And that’s where Ken is wrong. Just out of interest, I went to YouTube and entered, “how to make a whistle out of a willow branch.” It turns out there are still young people (and the young at heart) keeping this springtime tradition alive. And they’ve posted a slew of videos to show you how.

-30-